Softening User Rage Moments

You don’t start a tech revolution by choosing an easy topic. Many of our clients find that the most satisfying work is taking on the hard problems – the ones no one wants because they seem tricky to solve. And usually, if it’s a hard problem, it’s not just technologically tricky. The ones and zeroes are normally solvable given time and budget.

No, the kinds of hard problems I’m talking about involve painful moments in life. Car accidents. Health crises. Inability to pay for care. The decline and eventual passing of those we know and care for. No technological wizardry can save people from those difficult moments. But technology can certainly make it worse.

Most of us have experienced some form of this on the user side, and it never feels good. One example I remember very clearly was trying to cancel my pet insurance after my dear corgi Lucy passed away. The process in the insurance company’s online portal was so cold and unfeeling (and complicated) that I gave up and ended up paying for six months of insurance for my beloved departed girl because I didn’t want to face it again. I finally called Customer Service and got it cancelled. When I got our sweet boy Bruno, and later, our feisty Scarlett, I chose a different insurer.

Lucy, Bruno, and Scarlett

Why does this happen? Is it because the organization doesn’t care? In some rare cases, it could be. But what we see more often is that because they can’t solve the underlying life problem (for example, someone grieving a pet), they feel helpless and even fearful about trying to make it better and avoid the problem altogether.

First, do no harm

The first step is reframing the problem. In these cases, your goal is not to solve the problem. Your minimum objective is not to compound the problem.

Picture this: a user is going through a stressful event—they were just in a car accident. They can’t remember their username or password to log in to their insurance company’s website to get to crucial documents. Your chatbot on your website asks if they need help. They respond that they need help resetting their password. Your chatbot directs them to log in to make a support request. Huh? They can’t log in—they just said they don’t know their username or password.

This is a classic user rage moment. The kind of moment that burns so brightly in someone’s memory that they will cancel their service with your company just to get away from any further dealings with you. Your mission is to avoid these moments.

To do that, start by identifying the most likely rage moments in your user’s flow. Those might be related to your product, or they could be tertiary (in our example above, the car accident itself obviously was an exacerbating factor that’s tertiary to the technology itself). We could then map out that we expect that someone who is in an accident is going to need to file a claim and possibly access other important documents. They may not have downloaded the app yet. They might be newly registering, or they might be using the website or the app. If they had the app already, they might forget their password or username like our user. All of these are potential rage paths.

The good news is, you can solve every one of these without having to solve the underlying external problem that the user got into a car accident. The key is to recognize the path, map it out, and find those rage points. And then deal with them.

One more note about this: while UX sets the stage and covers probably 85–90% of this with up-front research and design, a good UX-enabled QA process is important too. That’s where you’ll find tricky issues that are only uncovered with real data. Ruthlessly test your flows for rage prevention. No dead ends. For us, this kind of QA is a key part of development and some valuable changes come out of the process.

Acknowledge the user honestly

Once you’ve identified the rage moment, the next step is doing something to correct it—and that’s where many companies’ UX short-circuits. It’s actually extremely simple to start to make it better: acknowledge the user.

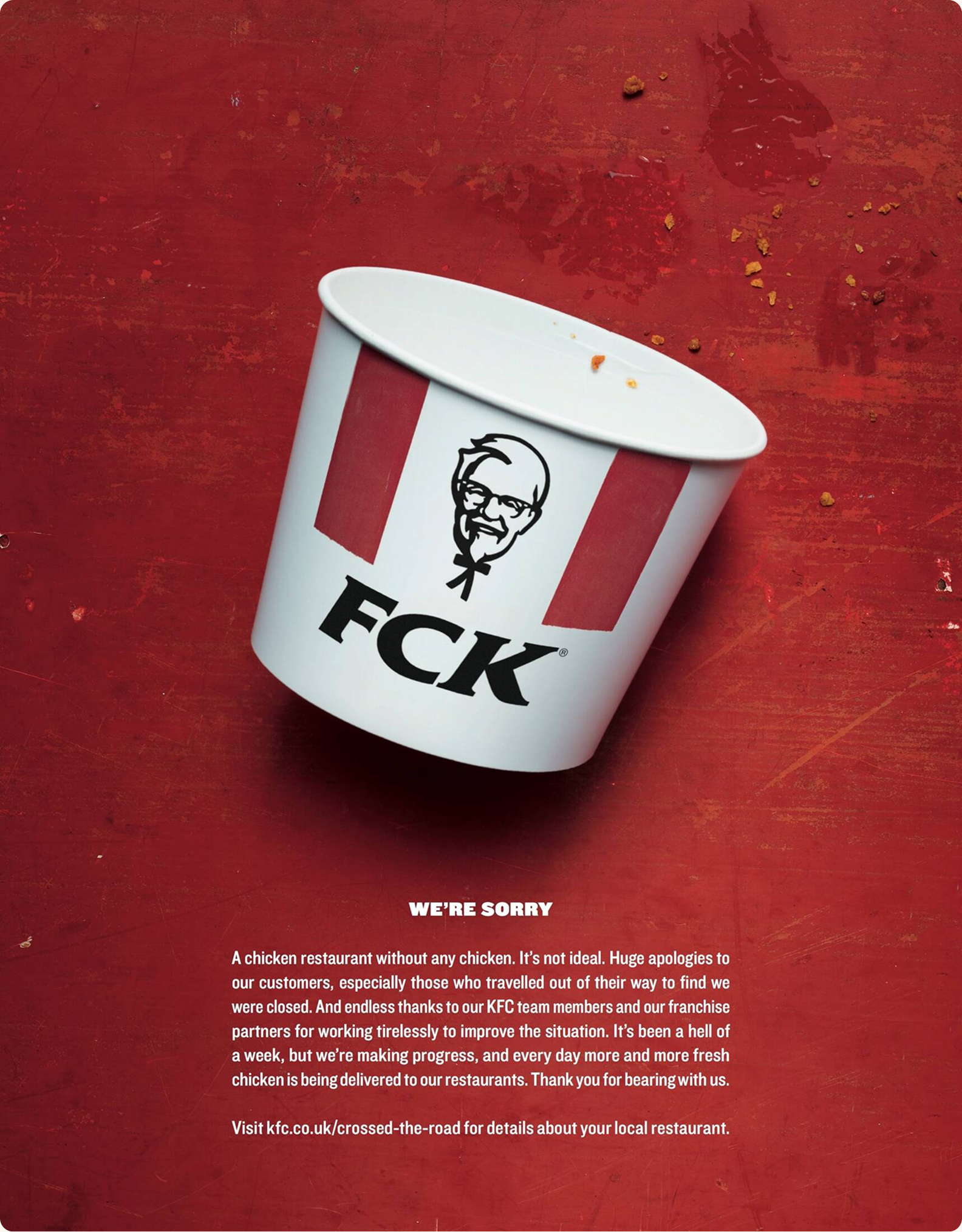

So many companies think that they can’t acknowledge when they’ve created a poor experience and can’t do anything to solve it. Acknowledging is an underrated magic bullet for a lot of these sorts of issues. My favorite example of this is when KFC in the U.K. switched logistics partners from Bidvest to DHL, and the new partner couldn't deliver on time, causing chicken shortages at KFCs in the U.K. and Ireland. People were irate. People apparently called the police. It was a spectacle, and a classic study in rage moments.

But then KFC did something unexpected. They took out the full-page ad shown below in major publications.

KFC’s apology ad.

This is skillful because in one ad they do a few things:

They acknowledge the problem.

They acknowledge the customers specifically, in clear and relatable language that sounds a lot like the way a real person would deliver a sincere apology.

They use humor.

They explain what they’re doing to make it better.

Please note that this ad could survive without #4, but remove any of the first three items and it would lose a lot of its impact. Humor is not appropriate for every single situation, but you’d be surprised how often it helps when the brand is the source of the problem (less helpful when we’re talking about one of those external difficult life moments, like the death of a loved one).

Abstracting that out, the general formula is:

Acknowledge the problem.

Acknowledge the user/customer specifically and directly. Talk to them like you would in real life, not with corporate platitudes like “We apologize for the inconvenience.”

Where appropriate, use humor (especially if your organization is the real or perceived cause of the issue).

If you have a path to fix it, share it.

I want to point out that acknowledging the problem and acknowledging the user/customer are separate steps. Acknowledging the problem is “We ran out of chicken.” Acknowledging the customer looks like, “Apologies to our customers, especially those who traveled out of their way.” They are specifically speaking to not only the problem but the customer’s pain.

The path forward

Once we’ve acknowledged the problem and the customer/user’s pain, we need to decide if there’s a path to get the user to a better place.

Many brands really overthink this. You do not need to provide a technological path for every edge case. Some things are simply too cumbersome and too rare to code for. But you do not leave those users behind. In one situation, we recognized that there was a case where users trying to change their email might get stuck if they had switched jobs and no longer had access to the old email. Due to security requirements, it wasn’t going to be possible to provide an unauthenticated path to do this, and we couldn’t rely on SMS. But what we could do was specifically call out the situation in a graphical element and ask people to contact customer service, with a button to do so instantly.

When there’s not a clear technological path forward, that sensitivity is often all it takes to avert peak rage moments.

In other cases, there is a tech-based path forward, but it might be lengthier than we want. Maybe a user needs to file an appeal or go through some sort of signup process that has several steps. In this case, honesty wins. One trick we often use is to time how long it really takes. Even a multi-step form often takes no more than a few minutes. Letting the user know that the pain is “2 minutes or less” can help alleviate anxiety.

There’s another unsung benefit to this: it builds trust. If you say it takes under two minutes—and it does—the user now knows that you will keep your word. Depending on your brand tone, you may also throw in empathy statements like “No one likes paperwork, so we’ll keep this short.” It acknowledges the pain point, puts the brand on the same side as the user, and reinforces the commitment to the user’s experience.

When it’s your fault (real or perceived)

We touched earlier on a situation with KFC where the user’s rage moments were the brand’s fault—at least indirectly. Technically, their supply chain was the issue, but they recognized that to consumers it was their failing. One additional thing they did right was that they immediately accepted responsibility and didn’t try to shift it.

That might feel vulnerable, and sometimes it may not be something your legal team allows. It’s not right for every situation. But when possible, try to be honest. You can mitigate some rage (and accomplish almost the same thing) by acknowledging that it’s difficult for you too (“It’s been a rough week.”)

Once you’ve acknowledged the difficulty, keep the focus on the client. If you have a way to prevent it in the future, or get back on track (for one-time events), or ways the user can prevent it as well, provide those options—but remember to stay compassionate. It’s probably not the moment for deep customer education. Save that for when they’re in a better state of mind.

There’s power in handling pain well

This might sound like unglamorous stuff, but it matters, and it can turn into a strength for your brand. Customers remember when they were treated well at a stressful time. Chewy famously sends cards when they’re notified owners’ pets pass away.

In a lower-stakes example, many of brands have started using light humor on their error pages, like the below 404 page from Discord.

You can’t erase a hard moment. But you can soften it. And in high-stakes tech products, that’s one of the most meaningful things we get to do.

Onward & upward.